Recent developments in a variety of sectors, including health care, research and the direct-to-consumer industry, have led to a dramatic increase in the amount of genomic data that are collected, used and shared. This state of affairs raises new and challenging concerns for personal privacy, both legally and technically. This Review appraises existing and emerging threats to genomic data privacy and discusses how well current legal frameworks and technical safeguards mitigate these concerns. It concludes with a discussion of remaining and emerging challenges and illustrates possible solutions that can balance protecting privacy and realizing the benefits that result from the sharing of genetic information.

There are many stories in the media highlighting the multitude of ways by which genomic data are now relied upon, including in basic research, clinical care, discovering relatives and ancestral origins, tracking down criminals, and identification of victims. At the same time, numerous reports from around the world illustrate that some people are concerned about how genomic information that relates to them are used, often stated as challenges to privacy. These apprehensions do have some foundation as people can suffer harm if data about them are used in ways they do not agree with, for example, to examine ancestry 1 or to create commercial products 2 without the individual’s approval, or if the data are used in a manner that causes an individual to suffer adverse consequences such as stigmatization 3 , disruption of familial relationships 4,5 or loss of employment or insurance. However, the law provides limited, patchy protection 6,7 .

The concept of privacy and its protection has many facets 8 . People may wish to control how genomic data about them are used but, in many cases, they only have the choice to opt in (or opt out) based on the terms contained in a consent form or a service agreement 9 , which frequently goes unread 10,11 . In other instances, people may not have any choice at all about how genomic data about them are used, such as when data are deemed to be anonymised in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) 12 of the European Union (EU), de-identified in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) 13,14,15 or considered non-human subject data in accordance with the Common Rule for the Protection of Human Research Participants 16 in the United States. Another aspect of privacy is the right to solitude (often voiced as the right to be left alone), a principle first formalized in legal circles in the late 1800s 17 , which could include the right not to be (re)contacted about ancillary findings generated from genomic testing or discovery-driven investigations into existing genomic data sets 18,19 or by previously unknown relatives 20,21 .

Yet, the right to privacy has never been absolute, in part because many uses of these data, such as clinical care, research, exploring ancestry, finding relatives and identifying criminal suspects and victims of mass casualties, can be valued by users, other stakeholders, or society at large. For example, even though physicians have strong ethical and legal duties of confidentiality that require them not to disclose patients’ information to others, these obligations are not unconditional because the law has created numerous exceptions such as for public health reporting 22 or in criminal investigations.

Although the tension between privacy and data utility raises an array of ethical issues 23,24,25 regarding when genomic data can be accessed and used, this Review focuses on the primary tools that are applied to define and protect these boundaries: law (as instantiated in statutes, regulatory regimes and case law), policy and technology. Several reviews on genomic data privacy have been published over the years in response to the evolution of approaches to intrude upon, and protect, privacy. Initially, Malin appraised the robustness of genetic data de-identification 26 . This study was followed by Erlich and Narayanan who analysed and categorized computational methods for re-identification, in light of new techniques for surname inference, and potential risk mitigation techniques 27 . Naveed et al. reviewed the privacy and security threats that arise over the course of the genomic data lifecycle, from data generation to its end uses 28 . Wang et al. studied the technical and ethical aspects of genetic privacy 29 . Arellano et al. reviewed policies and technologies for protecting the privacy of biomedical data in general 30 . More recently, Mittos et al. systematically reviewed privacy-enhancing technologies for genomic data and particularly highlighted the challenges associated with using cryptography to maintain privacy over a long period of time 31 . Grishin et al. reviewed the emerging cryptographic tools for protecting genomic privacy with a focus on blockchains 32 . Bonomi et al. reviewed privacy challenges as well as technical research opportunities for genomic data applications such as direct-to-consumer genetic testing (DTC-GT) and forensic investigations 33 . Similarly, numerous articles have addressed the incomplete and inconsistent protection that the law provides from harms to individuals and groups in different settings 3,19,34,35,36 .

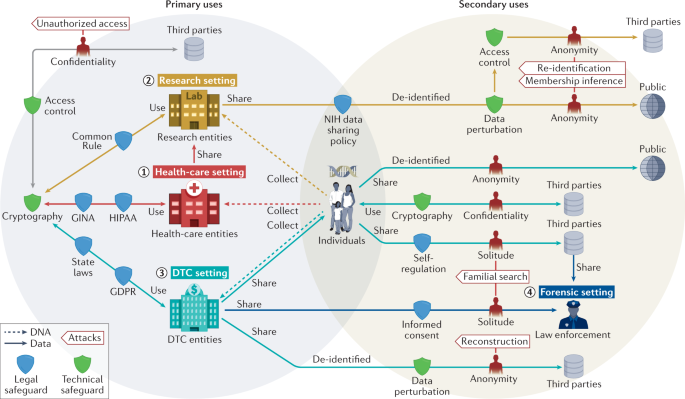

Our Review diverges from prior work in that we consider it essential to discuss the legal and technological perspectives together. This is because technological interventions can heighten, but also ameliorate, legal risks, whereas some laws provide control or protect people from downstream harm from data use, thereby opening the door to different and perhaps less stringent technological protections. Moreover, recent disruptions associated with mandates for data sharing 37,38 , the DTC-GT revolution and the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic — events that have dramatically accelerated the collection and use of genomic data 39,40,41 — have dramatically changed the social environment in which genomic data are obtained and used. Blending legal and technical protections in a holistic ecosystem of genomic data is challenging because protections are interconnected but vary in the environments in which they were developed, the stakeholders involved and their underlying assumptions. To demystify the connections among and the assumptions behind different legal and technical protections, we partition the ecosystem into four settings: health care, research, DTC and forensic settings.

In this Review, we begin with a brief overview of attacks on privacy in the context of genomic data sharing and subsequently discuss both how to mitigate privacy risks (through technical and legal safeguards) as well as the consequences of failing to do so effectively. Next, we categorize legal protections according to different settings since each setting tends to have unique laws and policies; meanwhile, we identify settings where each technical protection was first introduced and/or has been frequently applied. We consider the particular challenges that can arise in the research setting itself. We then note that genomics researchers also need an appreciation of the larger ecology of the flows of genomic data outside the research and health-care settings in light of their impact on data privacy and public opinion and thus ultimately on public support for genomic research. Thus, we discuss DTC-GT, the obligations that companies that provide these tests owe to users, and the consequences of use by consumers to find relatives and by law enforcement to find criminal suspects. For reference, Fig. 1 illustrates an overview of privacy intrusions and safeguards in the ecology of genomic data flows, and Table 1 summarizes various aspects of the technical literature featured in this Review. In our discussions, a first party refers to the individual to whom the data correspond, whereas a second party refers to the organization (or individual) who collects and/or uses the data for a purpose that the first party is made aware of. By contrast, third parties refer to users (or recipients) of data who have the ability to communicate with the second party only and might include malicious attackers. Examples of third parties include researchers who access data from an existing research study or a pharmaceutical company that partners with a DTC-GT company. We conclude with a discussion of what legal revisions and technical advances may be warranted to balance privacy protection with the benefits to individuals, commercial entities, researchers and society that result from flows of genomic data.

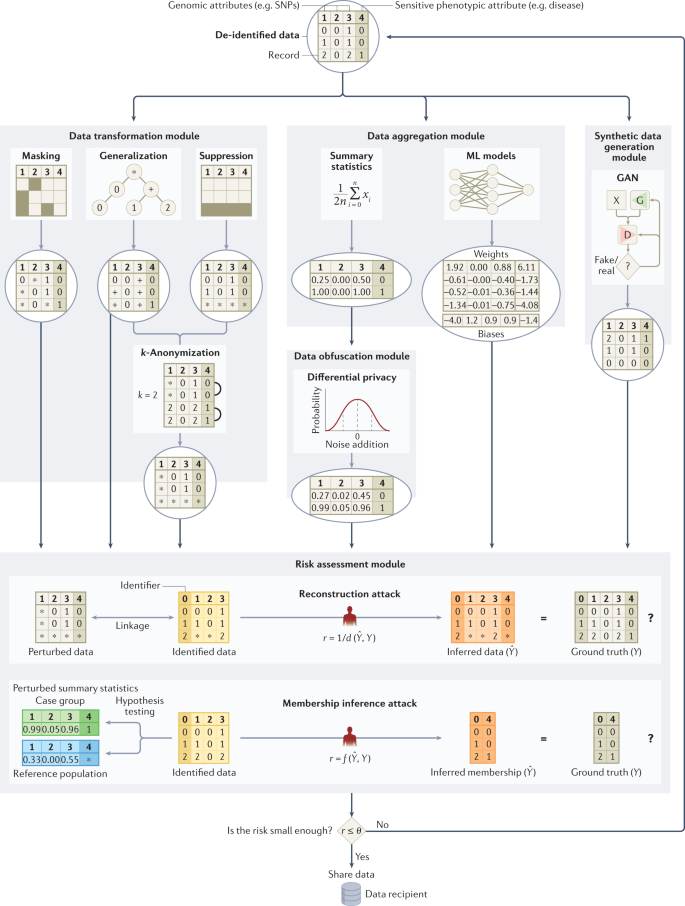

Some have suggested that the number of released genetic variants should be limited because, among millions of SNPs in a person’s genome, less than 100 statistically independent SNPs are required to identify each person uniquely 84 . However, protecting a genomic data set by hiding a set of genetic variants may not be very effective due to correlations among genetic variants (known as linkage disequilibrium) 85 and well-established genotype imputation techniques 86 .

To thwart re-identification through linkage in general, Sweeney introduced k-anonymity 87 , a data transformation model, to ensure that each record in a released data set is equivalent to no fewer than (k − 1) other records with the same quasi-identifying values (that is, those which can be relied upon for linkage). Initially developed to address demographics, it was subsequently shown that this model could be applied to genomic data by generalizing nucleotides into broader types based on their biochemical properties to satisfy 2-anonymity 88 . Another countermeasure based on k-anonymity was proposed 89 to thwart recent linkage attacks using signal profiles 90 and raw data from functional genomics (for example, RNA sequences) 89 . Still, given the high dimensionality of genomic data, strategies based on generalization or randomization 84 are unlikely to maintain the data at a level of detail that is useful for practical study. Thus, certain legal mechanisms, such as the HIPAA Expert Determination pathway, which we detail later on, tie the notion of de-identification to a re-identification risk assessment based on the capabilities of a reasonable data recipient 91 . For research, the utility (or usefulness) of genomic data should be maximized when subjecting it to a protection (or transformation) method. As such, Wan et al. demonstrated how to balance the tradeoff between utility and privacy using models based on game theory 92,93 .

Although restricting access to data resources, such as the database of genotypes and phenotypes (dbGaP) 55 , reduces privacy risks, it may also impede research advances. One potential alternative is a semi-trusted registration-based query system 94 that processes queries internally and releases only summary results back to the users instead of releasing all individual-level data. For example, Beacon services (for example, the Beacon Network), popularized by the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health (GA4GH), let users query for only one type of information within genomic data sets 95 , namely the presence of alleles. Although a membership inference attack against Beacon services was demonstrated by Shringarpure and Bustamante 96 in 2015 and enhanced later 97,98 , the effects of this attack can be mitigated by adding noise 99,100 , imposing query budgets 99 , adding relatives 101 or strategically changing query responses for a subset of genetic variants 102 .

Obfuscating, or adding noise to, summary statistics based on a computational model, such as differential privacy (DP), has been used to counteract membership inference attacks 103 . However, the role of DP is limited in protecting GWAS and other data sets 104,105 because a large amount of noise is required to provide protection 27 . Even if aggregate statistics are released with significant noise, membership and attribute information can still be inferred 106 . To preserve privacy, the resulting utility of the DP model is therefore often extremely low 61 . However, higher data utility could be achieved when assuming a weaker adversarial model 107 or combining DP with modern cryptographic frameworks (for example, homomorphic encryption (HE), which we detail later on) 108 .

Recently, researchers have proposed protecting anonymity by generating synthetic genomic data sets using deep learning models (for example, generative adversarial networks 109,110 or restricted Boltzmann machines 110 ). The generated data aim to maintain utility by replicating most of the characteristics of the source data and thus have the potential to become alternatives for many genomic databases that are not publicly available or have accessibility barriers.

The question of whether data are considered identifiable or not has important implications for deciding whether the individual to whom they pertain must give consent for their use. It is important to recognize that the laws regarding how genetic and genomic data are handled differ among countries. For illustration, we compare and contrast how regulations in the EU and the United States influence the use of such data.

International data privacy legislation is likely to alter the landscape of data privacy protection in genomics research around the world moving forward. The most notable example is the EU’s GDPR, which took effect in 2018 and places restrictions on entities that handle the personal information of citizens of the EU, including genetic information 12 . The regulations grant data subjects access and deletion rights, impose security and breach notification requirements on entities that handle personal information, and place restrictions on the use and sharing of data without informed consent. Since the GDPR was enacted, there has been heated debate about its impact on the flow of data and hence the conduct of genomics research. Shabani and Marelli, for example, focus on the GDPR’s recognition of the contextual nature of risk, and particularly the risk of re-identification, which they suggest can be ameliorated by compliance with codes of conduct or professional society guidance 111 . Mitchell et al. suggest that it may be necessary to have more stringent controls as well as to analyse data in place to avoid sharing 112 . In a subsequent news story, Mitchell also pointed out the complications posed by the emergence of identified ancestry databases 113 .

The United States has several laws that address the issue of identifiability, some of which have been in place for many years, and which differ in important ways both from each other and from the GDPR 113 .

One of the most important laws governing patient care and biomedical research is the HIPAA and its Privacy Rule, which is limited in its oversight to data in the possession of three types of covered entities (that is, health-care providers, health plans and health-care clearinghouses) as well as the business associates of such entities 114 . HIPAA generally requires these entities to obtain patient authorization for uses and disclosures of protected health information outside of treatment, payment, and health-care operations and conveys access rights to individuals 115 .

However, the protections provided by HIPAA even within ‘covered entities’ contain numerous exceptions 116 . In particular, HIPAA does not require permission to use or disclose health information, including genomic information, if it has been de-identified through either one of two mechanisms that are colloquially referred to as ‘Safe Harbour’ and ‘Expert Determination’. HIPAA defines de-identified data as follows: “Health information that does not identify an individual and with respect to which there is no reasonable basis to believe that the information can be used to identify an individual is not individually identifiable health information.” The Safe Harbour approach requires the removal of an enumerated list of 18 explicit identifiers (for example, names, social security numbers) and quasi-identifiers (for example, date of birth and 5-digit ZIP code of residence) 116 as well as an absence of actual knowledge that the remaining information could be used alone or in combination with other information to identify the individual. By contrast, the alternative Expert Determination pathway requires the application of statistical and/or computational mechanisms to show that the risk of re-identification is very small (a term not explicitly defined by the law) 117 . Notably, “biometric identifiers, including finger and voice prints”, are listed as one of 18 identifiers, which could lead to the argument that genomic data should be included as well but this issue remains unsettled.

The protections afforded to genomic information shared with researchers depend heavily on the entity carrying out the research and the nature of the information (for example, whether it is shared in identifiable form or is instead converted into de-identified or aggregated data). Human subjects research conducted or funded by agencies within the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and other federal departments is governed by the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (that is, the Common Rule), which was initially enacted in 1991 and most recently revised in 2017 (ref. 14 ). Under the Common Rule, such research is subject to oversight by an Institutional Review Board, and investigators must often obtain informed consent before biospecimens and the resulting data can be used for research, thereby enabling the individuals to whom they pertain to have some control over their use. Among many other elements, the regulations require that investigators disclose if they plan to use identifiable information 118 , to share identifiable data and samples broadly 119 , to return clinically relevant research results to participants 120 , or to perform whole-genome sequencing 121 .

Much research that utilizes genetic data qualifies as minimal risk under the recently revised Common Rule and could therefore be eligible for expedited Institutional Review Board review 122 and waiver of consent 123 . In addition, secondary research involving data that were initially collected for some other clinical or research purpose and has been transformed into a non-identified state (that is, data that have “been stripped of identifiers such that an investigator cannot readily ascertain a human subject’s identity”) 124 is currently exempt from Common Rule regulations altogether, especially since a proposal to consider biospecimens and DNA data as identifiable per se was explicitly rejected when the Rule was revised in 2017. Thus, informed consent is not required for such research, a result that is generally much more permissive than the exceptions permitted under HIPAA. However, regulations governing identifiability may change in the future as federal departments and agencies were charged with formally re-examining the definition of ‘identifiable private information’ and ‘identifiable biospecimen’ over time, expecting that emerging technologies, such as whole-genome sequencing, may make genomic data more easily distinguishable.

The courts in the United States, especially those at the federal level, have been reluctant to endow individuals with a right to control access to biospecimens or resulting data 125,126,127 or to extend legal protections to discarded DNA 22 . Moreover, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 (GINA) 128 , which nominally prohibits genetic-based discrimination in the context of health insurance and employment, is limited in its scope, applying only to asymptomatic individuals and offers no protection regarding other types of insurance (for example, life and long-term disability). The Affordable Care Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act fill only some of these gaps 6 .

By contrast, over the years, several US state legislatures have enacted laws that convey additional rights or protections to individuals with respect to genetic information about them. For example, some states have deemed genetic information to be the property of the individual being tested and/or require informed consent for genetic testing 129 . States may also impose security requirements for genetic data or other health records, regulate the retention of biospecimens and data, or convey additional protections to research participants. States, most notably California 130,131 , Virginia 132 and Colorado 133 , have adopted broad data privacy legislation that provides people with much greater control over some uses of information about them with yet-uncertain implications for genomic information in a variety of settings, including research 134 . Other states, including Florida 135 and New York 136 , are considering legislation as well. The highly influential Uniform Laws Commission, which proposes statutes for adoption, explicitly defined “genetic sequencing information” as sensitive and thus subject to special protections in its proposed Uniform Personal Data Protect Act approved in July 2021 by the Commission 137 . These proposed and enacted laws commonly grant more access and correction rights to individuals and impose more restrictions on the use and sharing of personal information without informed consent and thus approach more closely the structure of the GDPR 138 . Nonetheless, the differences among these statutes themselves and in relation to current federal and international law will doubtless further complicate compliance.

The primary focus of this Review is addressing the complex ethical, legal and technical challenges that arise in protecting privacy in genomic research. Focusing solely on genomic research fails to take into account the potential impact on privacy of the increasing availability of such data in other settings. A wide variety of individuals and entities now collect, use and share genomic data at an unprecedented level. As a result, these data are becoming an increasingly viable resource for parties who might wish to exploit the data, including not only researchers, but also employers, insurers, law enforcement and other individuals 33 , many of whom have garnered much more media attention than those conducting biomedical investigations. Numerous studies suggest that some people are worried about where genomic data about them go and how they are used, potentially affecting them in ways they neither desire nor expect. In addition to more commonly explored fears of discrimination 3 , this information can also redefine family relationships, for example, by confirming or disproving paternity, locating previously unknown relatives, or identifying anonymous gamete donors 139 . These concerns about use and impact, generally couched in terms of desire for genetic privacy, may affect individuals’ willingness to undergo clinical testing or to participate in research 3,140 . Such reluctance due to privacy concerns, in turn, may exacerbate existing health disparities and stifle scientific progress. Thus, when they design, conduct and discuss their research, investigators need to consider how genomic data are used and how the type of use affects whether or not the data are controlled outside the research setting as well.

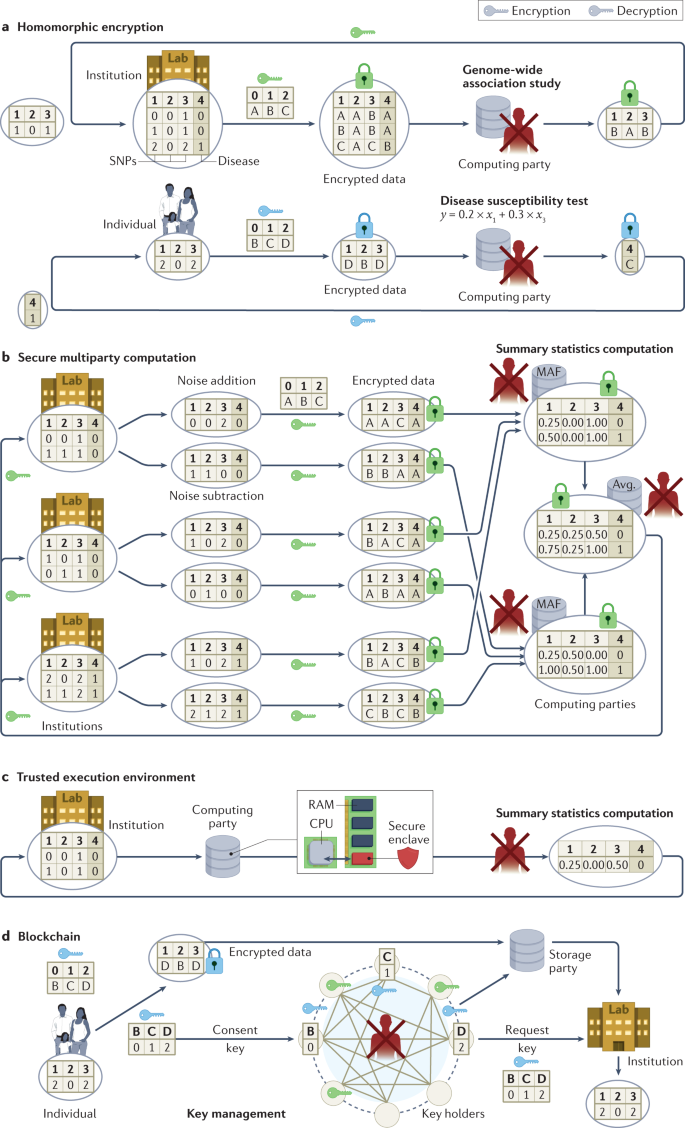

Researchers often use genomic data accompanied by an array of phenotypic and other information, which they may obtain from individuals directly, through health-care providers or from third parties such as DTC-GT companies. A researcher may also transfer data to third parties for computation or collaboration purposes. Many cryptographic tools can be deployed to protect such use of data from unauthorized access 29 . Figure 3 illustrates four cryptographic protection approaches with examples in the context of genomic data use cases.

Specifically, Fig. 3a illustrates a use case in which an institution that lacks computing capability outsources a computation task (for example, GWAS) to a third party while keeping the data encrypted. Homomorphic encryption (HE) enables computation on encrypted data sets without ever decrypting any specific record and can be utilized when the computation of statistics (for example, counts 141 , chi-square statistics 142 and regression coefficients 143 ) is outsourced to external data centres or public clouds 144 .

To generate statistically meaningful findings in the research setting, GWAS need many thousands of records that are often distributed among multiple repositories across various institutions, and even across jurisdictions. Secure multiparty computation (SMC), unlike HE, enables multiple parties to jointly compute a function of their inputs without revealing inputs 28 , as illustrated in Fig. 3b, in which three institutions jointly compute summary statistics (for example, minor allele frequency) over their private data sets. SMC enables the computation of GWAS statistics over distributed encrypted repositories without the local statistics being released 145 , and it can facilitate quality control and population stratification correction in large-scale GWAS 146 . SMC can also be applied to sequence matching in other settings 147,148 . Compared to federated learning, which enables multiple parties to jointly train ML models on genomic data sets over local statistics 149 , SMC guarantees a much higher security level at the cost of computationally expensive encryption operations. To reduce both the computation overhead and the communication burden, SMC can be combined with HE to support GWAS analyses among a large number (for example, 96) of parties 150 .

Cryptographic hardware can be leveraged to reduce the burden of computation (for example, secure count queries) 151 on encrypted data using HE or SMC 152 . For example, a trusted execution environment based on Intel Software Guard Extensions (SGX) isolates the computation process in a protected enclave on one’s computer 153 , as illustrated in Fig. 3c, in which an institution outsources the task of computing summary statistics (for example, minor allele frequency) to a third party. Combining hardware (for example, Intel SGX) and algorithmic tools (for example, HE 154 or sketching 155 — a data summarization method) can enable users to perform secure GWAS analyses efficiently.

Blockchains can be adopted to incentivize genomic data sharing 156 while protecting privacy 32,157 . For example, researchers have proposed to use blockchains to securely share GWAS data sets 158 or parameters of ML models trained on genomic data sets 159 . Figure 3d illustrates a distributed data sharing system, in which multiple independent parties hold shares of a split decryption key and maintain a blockchain that receives data access requests from researchers and consent from individual participants 32 . Combined with HE and SMC, blockchains can enable privacy-preserving analysis on genomic data in a personally controlled 160 and transparent manner 161 . However, numerous practical challenges with blockchains remain, including scalability, efficiency and cost 157 .

Countries around the world have put in place provisions regarding the protection of human research participants, which typically address the need to weigh the risks and benefits to participants, particularly for those who are vulnerable, to assess the scientific merit of protocols, to protect privacy and confidentiality, and to define the role of oversight by research ethics committees and the role of informed consent 162 . Although the details differ across countries, the most recent version of the Declaration of Helsinki, the foundational document for international research ethics, generally requires consent only for “medical research using identifiable human material or data” 163 . The Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences addressed this issue in greater depth in Guideline 11 of its most recent report in 2016 on International Ethical Guidelines for Health-related Research Involving Humans 164 .

More generally, several international laws influence the ability to access or share genomic data. As noted above, the GDPR provides individuals with substantial control over data about them, typically requiring consent for use and often forbidding the transfer of data to countries whose data protections are not substantially compliant with the GDPR 165 . Citing several national and individual interests, China heavily regulates when human genomic data can leave the country and requires governmental approval 166,167 . India 168 and many countries in Africa 169 have similar practices.

The United States lacks an overarching national data privacy policy and does not typically impose limits on the export of genomic data 170 . Moreover, the legal protections afforded to genomic information shared with researchers depend heavily on the entity carrying out the research and the nature of the information (for example, whether it is shared in identifiable form or is instead converted into de-identified or aggregated data) as discussed above.

In recent years, the use of genomic data in non-research settings has garnered an enormous amount of public attention and can have important implications for personal privacy.

Millions of US residents have undergone DTC-GT with companies that purport to provide personal information about a variety of issues, including health, ancestry, family relationships (for example, paternity), and lifestyle and wellness 171,172,173 . There are numerous media stories about how consumers use these data to reveal biological relationships, uses that elicit complex responses 139 , both positive and negative. Some people are pleased to find new relatives or to uncover their biological origins, whereas others are distressed by the results or by unwanted contact. There are, however, virtually no legal constraints on how consumers may use these data, although the legal consequences that may result from their actions could be considerable, including divorce and efforts to avoid support for children 19 .

The companies offering these services generally fall outside of the purview of the Common Rule and HIPAA (being neither federally funded nor a HIPAA-covered entity, respectively). Instead, the flow of genetic data in the DTC setting is governed largely by self-regulation and notice-and-choice in the form of privacy policies and terms of service 172,173 . Recent surveys of the privacy policies and terms of service of DTC-GT companies reveal tremendous variability across the industry, with many companies failing to meet best practices and guidelines concerning privacy, secondary uses of genetic information, and sharing of data with third parties 172,173,174 .

Although the industry has largely been left to self-regulate, federal agencies have played a limited role in shaping policy with respect to DTC-GT. For example, the US Food and Drug Administration has exercised oversight over a narrow category of DTC health-related tests, although the trend has been to allow these tests to enter the market with little resistance 175 . The baseline of protection is provided by the Federal Trade Commission, which has the authority to police unfair and deceptive activities across all areas of commerce. Perhaps hindered by its broad mandate and limited resources, the agency to date has only intervened in the DTC-GT space in one case of particularly egregious conduct (that is, unsubstantiated health claims coupled with a lack of security of consumer personal information, including genetic data) 176 . Instead, the agency has chosen to embrace self-regulation, largely limiting its involvement to the issuance of consumer-facing bulletins 177,178 about the implications of genetic testing and broad guidelines for companies offering DTC-GT in the form of a blog post 179 . For those who are interested, numerous technical strategies exist to permit two users to match genome sequences without disclosing their genomes by using HE 180 , private set intersection protocols 181 or fuzzy encryption 182 , thereby providing additional privacy protections.

Importantly, millions of people have downloaded their results from DTC-GT and posted them on third-party databases to facilitate finding relatives or to obtain health-related interpretations. These sites are rarely subject to any type of regulation beyond what they specify in their terms of service 173 . Moreover, these sites reserve the right to change their practices, which may occur as a response to public pressure, but may also be due to changes in business operations. These are the data that facilitate forensic use and are likely to pose the greatest potential for re-identification of genomic data.

Law enforcement looms large in public opinion about genetic data since it may seek to access genetic information, an issue that has gained intense interest in the wake of high-profile cold cases that were ultimately solved using such information 183 . Over the years, there has also been an effort to expand government-run forensic databases at the federal, state and local levels 184 . The FBI currently maintains a nationwide database, the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS), that contains the genetic profiles of over 20 million individuals 185 who have been either arrested or convicted of a crime as well as over 1 million forensic profiles derived from crime scenes 186 .

Law enforcement may also seek to compel the disclosure of genetic information held by an individual or an entity such as a health-care provider, DTC-GT company or researcher. A subpoena is generally all that is required to compel disclosure of genetic information in a patient’s electronic medical record under HIPAA 187 . Genetic data held by researchers may be shielded by government-issued Certificates of Confidentiality, which purport to assure participants that such data are immune from court orders and outside the reach of law enforcement, but these are issued by default only to research funded by the NIH and other agencies within HHS and may not protect research data that are placed in participants’ electronic health records as well as disclosures required by federal, state and local laws 188,189 .

Furthermore, law enforcement may also seek to exploit public databases or utilize the services of a DTC-GT company for forensic genealogy purposes in FGG/IGG. To date, law enforcement in the United States has largely focused its efforts on publicly accessible databases (for example, GEDmatch) 183 and private databases held by companies that voluntarily cooperate (for example, FamilyTreeDNA) 190 . For example, law enforcement generated leads in dozens of cold cases by uploading genetic profiles derived from crime scenes to GEDmatch, a public database where individuals can upload their DTC-GT data to learn about where their forebears came from and to locate potential genetic relatives. Similarly, FamilyTreeDNA provides law enforcement access to a version of their Family Finder service, which, like GEDmatch, allows consumers to upload DTC-GT data to locate potential relatives.

In response to public privacy concerns, both GEDmatch and FamilyTreeDNA changed their policies to either require consumers to opt in for their genetic information to be used for law enforcement matching or provide an opportunity to opt out, rather than allowing such searches by default 68 . This change dramatically reduced the pool of users available to law enforcement, leading them to seek court orders to explore the entire databases of GEDmatch and Ancestry.com, respectively 187,191 .

In 2019, the US Department of Justice released an interim policy statement designed to signal its intentions regarding privacy and the use of FGG/IGG 192 . The interim guidelines, which have not been updated since, impose several limitations on federal law enforcement agencies, such as limiting these searches to investigations of serious violent crimes (ill-defined in the guidelines), requirements barring deception on the part of law enforcement when utilizing a DTC service, and requirements that the company seek informed consent from consumers surrounding their cooperation with law enforcement 192 . At least one local district attorney’s office has developed, and voluntarily adopted, similar guidelines 193 . Given the recent emergence of these tools, it is perhaps of little surprise that legal regimes are evolving in different ways across the country and around the world 194,195 .

At the same time, there has been limited research into techniques to mitigate kinship privacy risks 196 stemming from the familial genomic searches at the core of FGG/IGG. One general approach is to optimize the choice of SNPs that are masked to minimize the likelihood of successful inference based on relatives’ genomic information 196 , but little follow-up work has been done on this topic.

As this Review shows, providing appropriate levels of privacy for genomic data will require a combination of technical and societal solutions that consider the context in which the data are applied. Yet, there are challenges to achieving such goals. From a technical perspective, for instance, it is non-trivial to move from privacy-enhancing and security-enhancing technologies that are communicated in a paper or tested in a small pilot study to a full-fledged enterprise-scale solution. This challenge is not unique to genomic data as it is a dilemma for data more generally and for the application domains in which data are applied. In addition, one of the core problems is that it is difficult to build privacy into infrastructure after it has been deployed. Rather, privacy-by-design 197 , whereby the principles of privacy are articulated at the outset of a project or the point at which data are created and are tailored to the environment to which they are shared, may provide a more systematic and sustainable approach to genomic data protection. However, even if the principles are clearly articulated, there is no guarantee that the technology will support privacy in the long term. For instance, HE, one of the technologies emerging for secure computation over genomic data, is constantly evolving. This may make it difficult to compare genomic data encrypted at one point in time with genomic data created under a more recent version of the technology. Moreover, encryption technologies are not necessarily ideal for long-term management of data 198 , especially since new computing technologies, such as cheap cloud computing and quantum computing, might make it extremely cheap to crack such encryptions.

Beyond technology, numerous social factors, which inevitably involve tradeoffs between protection and utility, further complicate efforts to protect genomic privacy. Countries, for example, vary dramatically in how much control individuals have over how genomic data about them are used. Some provide individuals granular control while others permit use without consent in many settings, albeit often with stringent security protections. More dramatic is the impact of the growing number of people who post identified genomic data about themselves so that they can find relatives or connect with people who have similar conditions or history. Yet, people who share identified data about themselves increase the potential to re-identify other data about them. In addition, they also reveal information about their relatives, some of whom might have preferred more privacy. These consumer-created databases, unlike medical and research records, frequently have few limitations on use by third parties as has been illustrated by the growth of forensic genealogy. Deciding how to make tradeoffs between protection and use across the entire ecology of genomic data flows requires consideration of both the value of these interests as well as practicable mechanisms of control.

Pressure is growing to protect genomic privacy with security-enhancing technologies and legal regimes for use of genomic data. Nonetheless, it seems clear that simply giving individuals granular control over genomic data that pertain to them, by itself, while attractive to some, risks reifying an unwarranted fear of genomics and is likely to disrupt a wide array of advances in ways that almost surely do not align with the public’s preferences. What may well be needed is a combination of notice and some choice, accountable oversight of uses, and real penalties — both economic and reputational — for inflicting harm on individuals and groups. An additional requirement could be the creation of secure databases for specific purposes (for example, research versus ancestry versus criminal justice) with privacy-protecting tools and individual choice for inclusion that is appropriate for each, which can take the form of law 39 as well as private ordering using tools such as data use agreements 36 . Creating such a complex system will not be elegant and will need to evolve in response to how new laws and privacy-enhancing technologies affect individuals and groups, but simple solutions will not suffice either to protect people and populations from harm or to advance knowledge to improve health.

The authors would like to thank their colleagues at the Center for Genetic Privacy and Identity in Community Settings (GetPreCiSe) at Vanderbilt University Medical Center for their constructive feedback. This work was mainly sponsored by GetPreCiSe, a Center for Excellence in Ethical, Legal and Social Implications (ELSI) Research, through a grant from the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health (RM1HG009034). This work was also funded, in part, by the following grants from the National Institutes of Health: R01HG006844 and R01LM009989.